Strategy for Directors: Models

Following on from the great IoD course on finance, I did their Strategy for Directors course. I have split my notes into two parts. In this post, I will go through some models, with explanations. Then, in part 2, on Wednesday, I will tie it together.

If you prefer to watch rather than read, I covered a lot of this in my talk Analysing, Deciding, Doing: How to develop and execute an effective strategy.

The value of the models is in the discussion

For all of these models, the value is in bringing the issues into the open and discussing them, as much as the end result. People are often making unconscious assumptions about the future, or the current situation, and these models help surface them.

PESTLE

This is the first of the models for diagnosing your situation. PESTLE helps identify external influences.

Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal, Environmental.

For each area, come up with factors that might affect your company or project. Score them for certainty and impact.

Something that is certain to happen and will have a high impact (for example, GDPR) is something you need to respond to or capitalise on. Something that might not happen, or might have a relatively low impact, you will respond to in a different way, for example do some experimentation, or decide to just watch and wait.

As well as thinking about the factors, think about the trends in that factor. Not much changes over a couple of years but a lot changes over a decade.

VUCA

VUCA stands for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous.

It describes situations that defy predictability. If you are operating in a VUCA environment, you need to be able to flex your strategy.

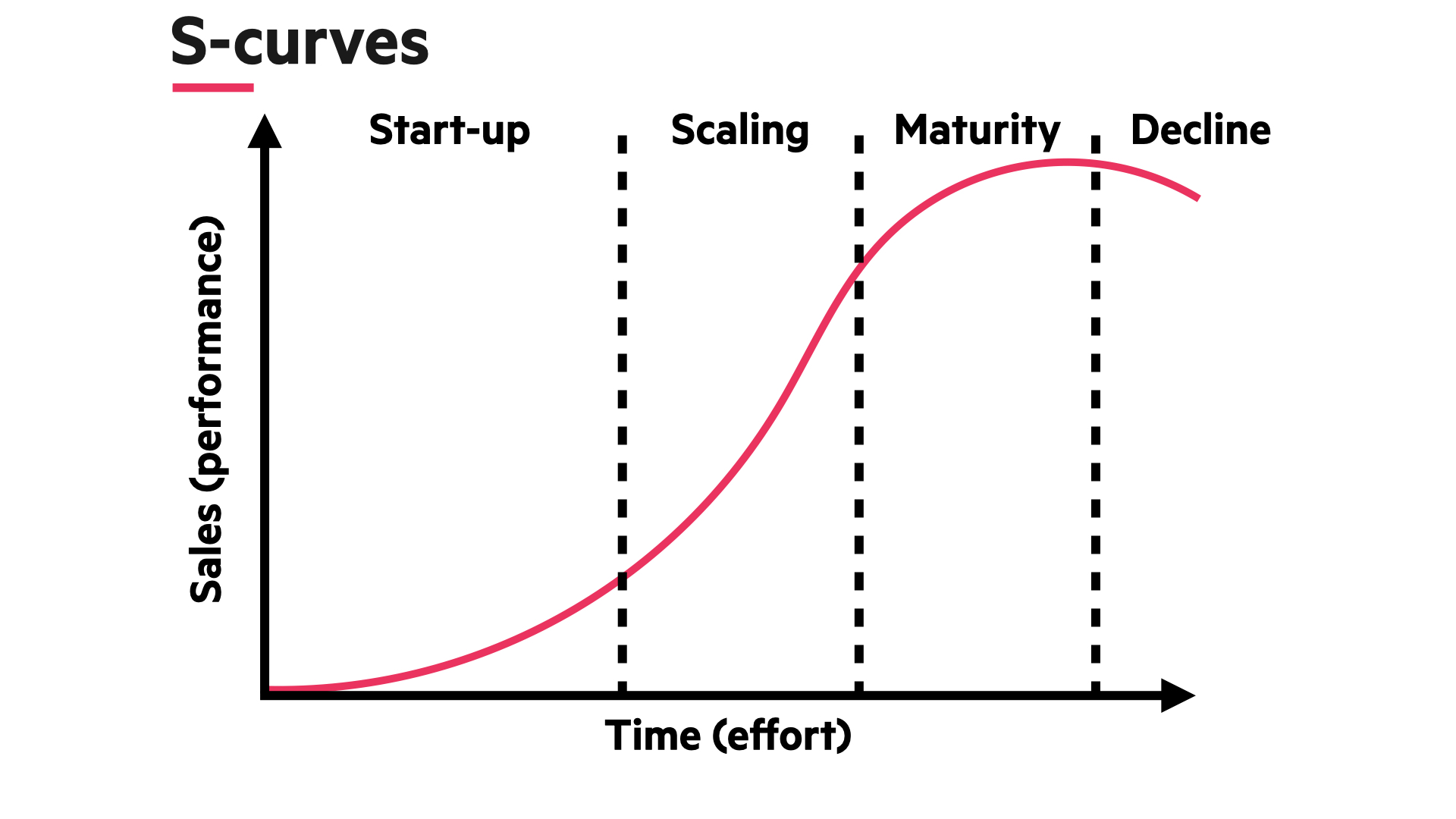

Market lifecycles: S-curves

The S-curve visually represents the market lifecycle: the evolution of a technology or business model. The stages are:

- Start-up: circumstances create an opportunity, e.g. a technological breakthrough. This phase involves experimentation; the possibility of achieving first-mover competitive advantage, and there may not be one agreed way to achieve the outcome (there may not be a “dominant recipe”).

- Growth/scaling: the initial opportunity has become a reality. There is likely to be a dominant recipe and growth may be substantial. Failing to exploit the opportunity gives an advantage to others. Scaling is about evaluating how much bigger the opportunity will become and by when; and here large companies with access to capital, brand traction and distribution networks are well placed, so smaller companies may seek their resources to facilitate scaling.

- Maturity: the strategic challenge evolves from being one of scaling to being one of competing. Energy in the market slows; many competitors with similar propositions are present. Differentiation is harder to find, so rivalry intensifies, e.g. with price competition. The peak on the S-curve is market saturation. The main concern is how to make the most of opportunities before decline begins.

- Decline: other opportunities have arisen and the issue is now when to withdraw from the market. Specifically, how long to spend exploiting the market, with an opportunity cost of shaping or being in the next market.

S-curves can be long, e.g. cement, or short, e.g. fast fashion.

Market segmentation

The total potential market for an organisation is made up of people who have needs or wants the organisation can meet and who have the ability/authority to pay for the goods/services.

Organisations are unlikely to serve all potential customers with the same offering. Segmentation is the slicing of a market into sections, e.g. by geography, size of customer base, purchasing power, etc.

Strategically the organisation needs to choose which segments it needs to capture and retain and which it can ignore. Analysis of segments should include quantitative insights (e.g. total potential buyers, usage patterns, cost of access to that market) and qualitative (e.g. customer attitudes to your service, brand loyalty to competitors).

Segmentation allows you to allocate resources to the areas they can be most effective and tailor marketing more precisely.

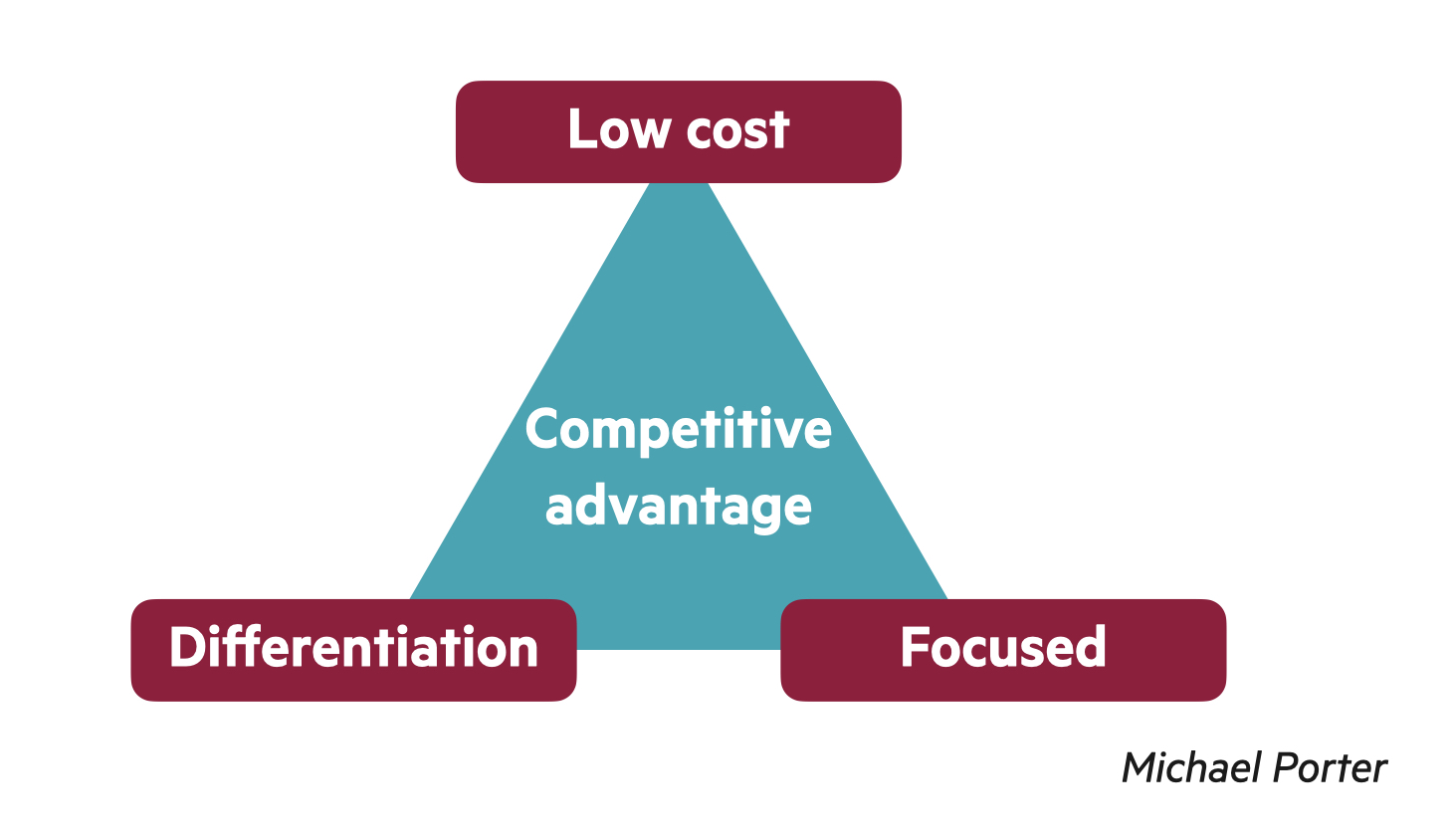

Strategic positioning – generic strategies

The goal is competitive advantage. But you need to be clear about what your strategic positioning is.

Positioning is what’s presented as valuable to customers: why should they buy your product/service? You offer the best value possible, and a perceived difference from the competition.

Michael Porter summaries it as: there are only three generic strategies for competitive advantage: low cost, differentiation (i.e. uniquely desirable products and services) and focus (i.e. a specialised service in a niche market).

The positioning can change along the product life-cycle, or as a strategy.

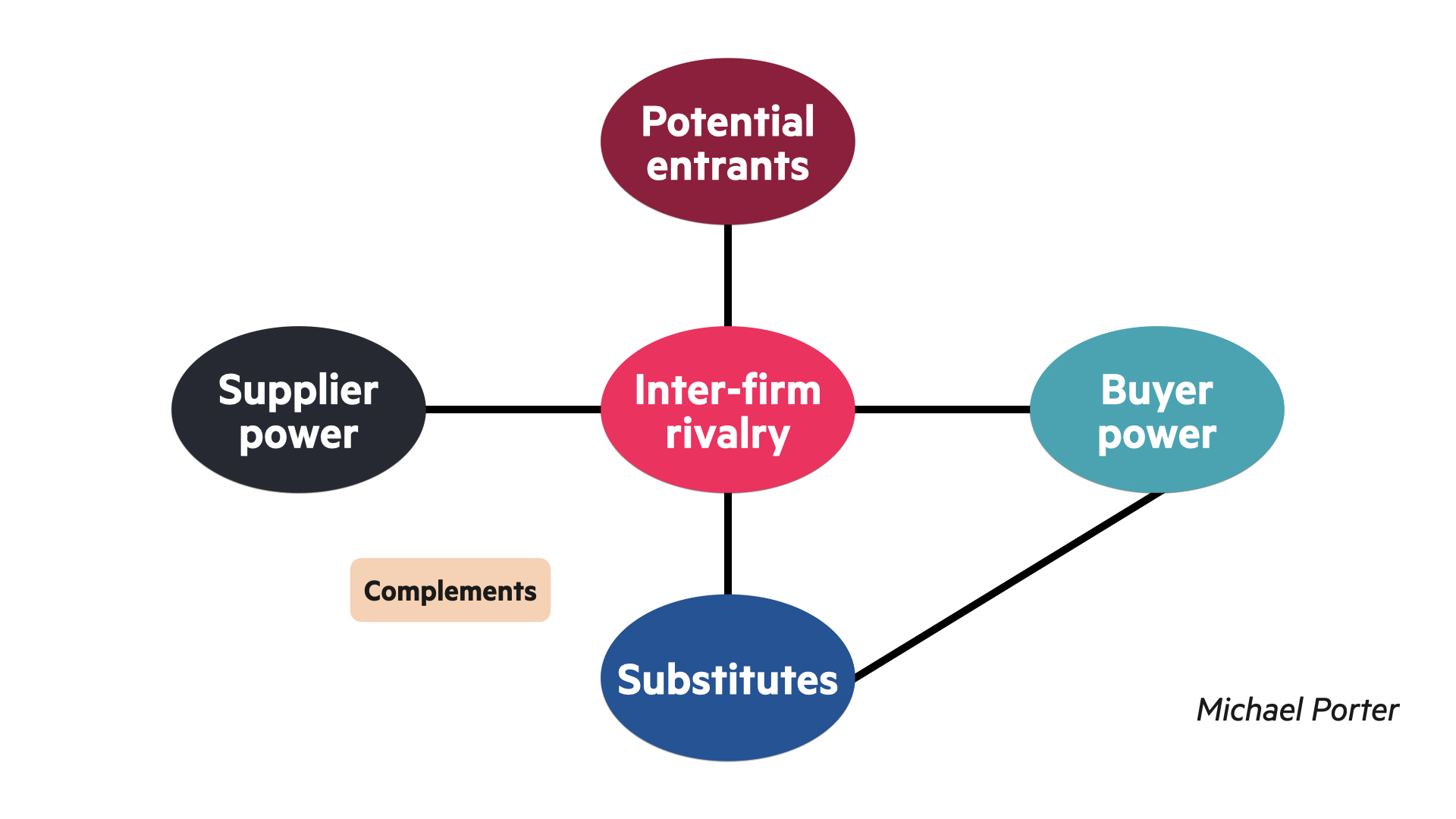

Five forces analysis

Within each industry, there is competition in different areas. Michael Porter outlined five forces with the potential to affect profitability. The forces can act individually or together, and they impact an organisation’s ability to create value.

- Inter-firm rivalry The more direct competition there is, the greater the downward pressure on goods and services. This force can be made worse by slow growth, low differentiation, low switching costs for buyers.

- Supplier power Suppliers might be stronger when there are high switching costs to new suppliers; the input/performance of the supplier is significant to the customer; or the buyer is not an important customer. The more power the suppliers have, the greater the cost to the organisation.

- Buyer power The more power buyers have, the less they will pay. Buyers might be stronger when there are low switching costs for buyers; viable alternatives and solutions exist; or there is a high volume or value of purchases by individual buyers.

- Potential entrants Profitable industries are likely to attract new competitors, so companies should think about how their advantageous position can be protected. High barriers to entry, which can deter new entrants, can include: significant capital required to start up or run; need for accreditation; effective product differentiation (including strong brand identity); high switching costs for customer; external influences favouring industry competitors, e.g. government policy.

- Substitutes An alternative method of solving a user’s problem, e.g. an e-bike instead of a car. The higher the threat of a substitute, the greater the downward pressure on prices. The source of the substitution is difficult to predict because it can rely on innovation in areas unrelated to your industry.

You use the five forces analysis to work out your best competitive strategy. This might include withdrawing from a market where the pressures are too great. It can work well overlayed onto a PESTLE analysis.

For most organisations, the most important relationship is buyer power.

There is also the idea of a sixth force, ‘complements’. These are products/services that enhance the competitive position of a business. The classic example is smartphones and apps. They are produced by different companies but apps enhance a smartphone and a smartphone enables apps.

Next: internal analysis

So far, these are all models of analysing factors external to the company, but it’s important to also look internally, to help understand what resources we have at our disposal.

Capability

Capability is what can the organisation do. It manifests itself in what is produced.

Capability is the combination of competence – the ability to do something well – and capacity – the amount that can be done.

Capabilities can be tangible and easily measured, like what machinery exists in the factory, what processes and systems are in place, location, etc, but can also include non-tangible elements, like culture, relationships, knowledge, brand.

When you look closely at each element of capability, that uncovers the underlying strengths and weaknesses of the organisation and allows you think about whether it has the right tools to be relevant to the external environment and how well value can be added. A healthy organisation is one that can successfully manage capability to do what needs to be done now, and to be able to change to meet the demands of the future.

One of the most important aspects of capability is that it needs to be coherent; for example, you will struggle if you have great resources but an ineffective communication process or a conflicting organisational structure.

Core competence

A core competency is something that differentiates your company and allows you to establish leadership in that area, for example the design of how something works. Core competencies provide access to multiple markets, make a significant (rather than marginal) impact on the customer benefit, and should be difficult for competitors to imitate.

You can’t rely on them because of the speed of innovation, but you should monitor them and how well they are embodied in your core products and how well they are creating value for the customer.

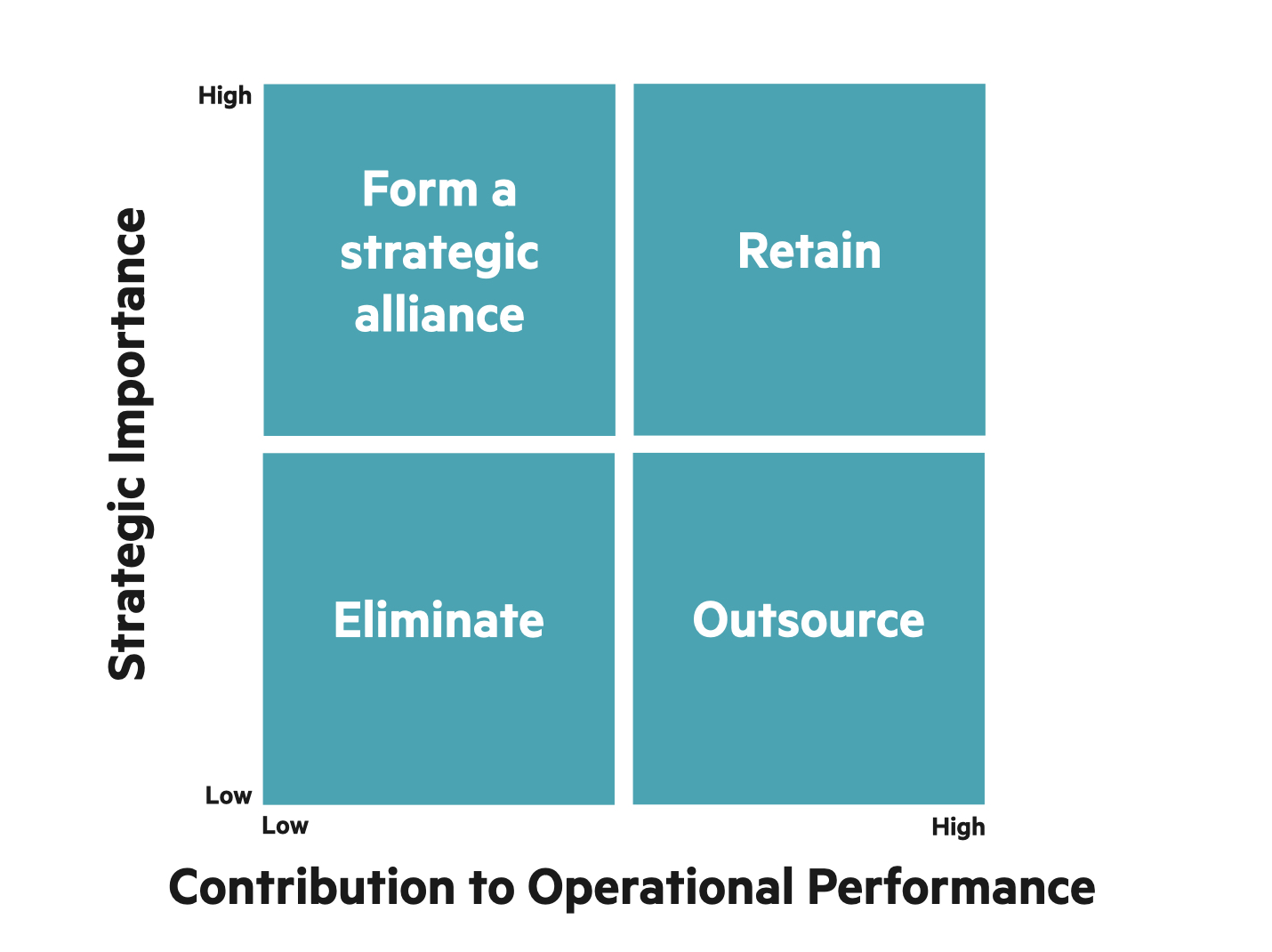

A diagram I really like, relates to core competencies.

If something is a core competency, it should be both of strategic importance and also contribute to operational performance, and you should retain it/build it in-house.

If it’s not a core competency, you should be looking to partner (high strategic importance, low contribution to operational performance), outsource (low strategic importance, high contribution to operational performance) or eliminate (low on both).

Threshold and distinctive capabilities: VRIN

Threshold capabilities are what’s required to participate: table stakes. Distinctive capabilities are what gives a competitive edge. Over time, as competitors innovate and the market matures, distinctive capabilities become threshold.

Another acronym, VRIN, is about what makes a capability distinctive:

Valuable – possible to monetise

Rare – scarcity is a route to being distinctive

Inimitable – hard to imitate

Non-substitutable – unlikely to be undermined by alternative approaches

A good example of this is when the iPod was created. Apple bought all the production capacity for small hard drives. Valuable because there was a market for it. Rare because they’d bought it up. Inimitable because smallness is the selling point. Non-substitutable because you don’t want to carry around 50 CDs.

That distinctive capability became threshold because it became a commodity, everyone could use small hard drives, and now irrelevant because now everyone uses flash storage.

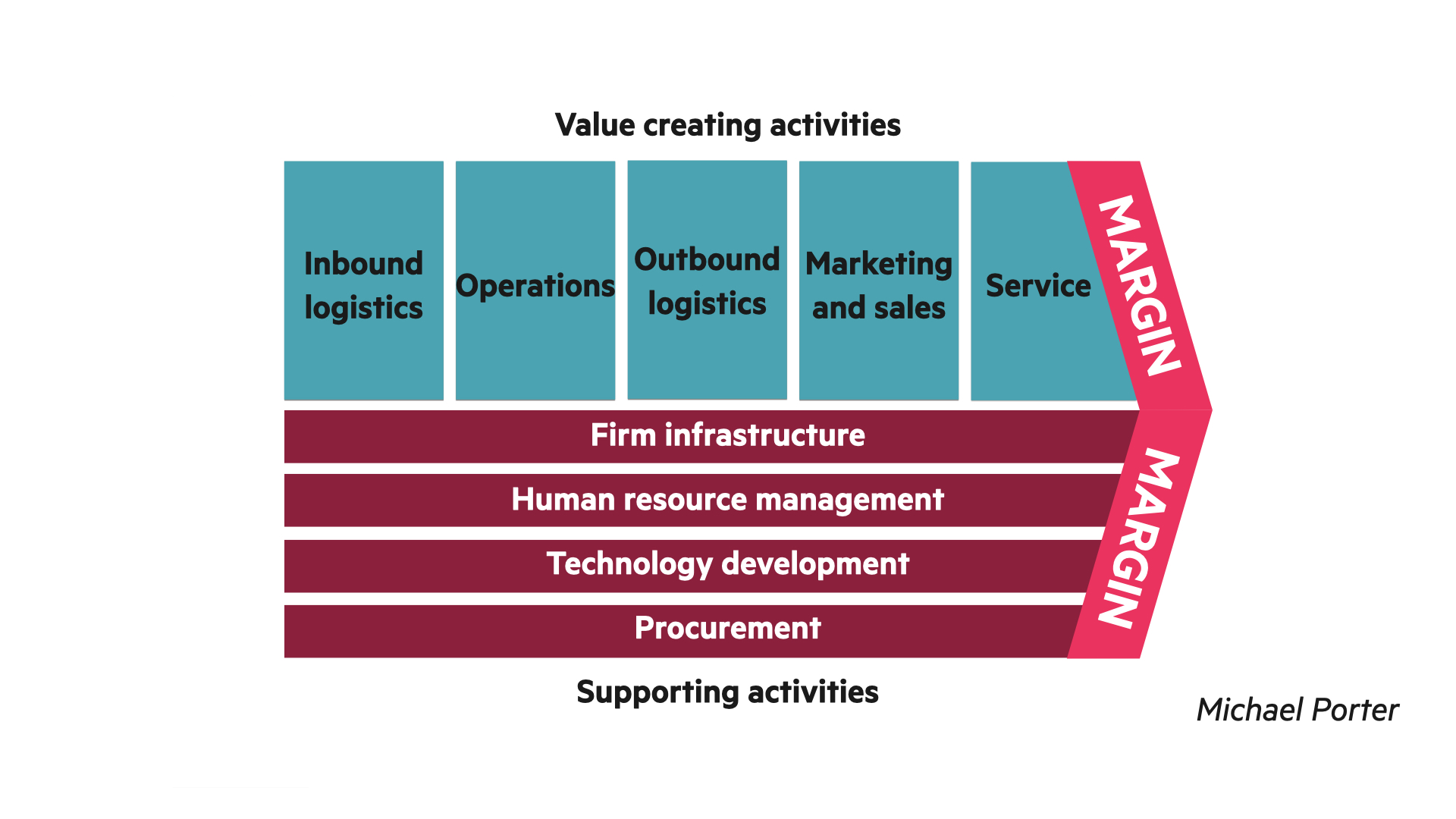

Value chain analysis

In a value chain analysis you look at all the activities you do in your business. Some will be value-creating, such as customer service, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and some will be supporting, for example procurement processes and HR.

In a value-chain analysis, you look at all of the value-adding activities and judge how much value is added to the customer at each stage. You can then decide where to focus, invest, cut costs, etc. Specifically: what can be done to add more value at each stage? This is a great activity for technology because at every stage you can add productivity or efficiency, as well as adding value.

For example, the value of elite fashion is in the design, brand marketing and service, not with making the actual garments. All manufacturing is executed in lower-cost regions of the world.

You first need to create the diagram for your own organisation. This model is from 1985; these days it will be much more rare for technology development to be a supporting rather than value-adding activity.

Bringing it all together: portfolio analysis

Now you’ve analysed the external world and explored the internal aspects of your organisation you bring it all together for an integrated picture.

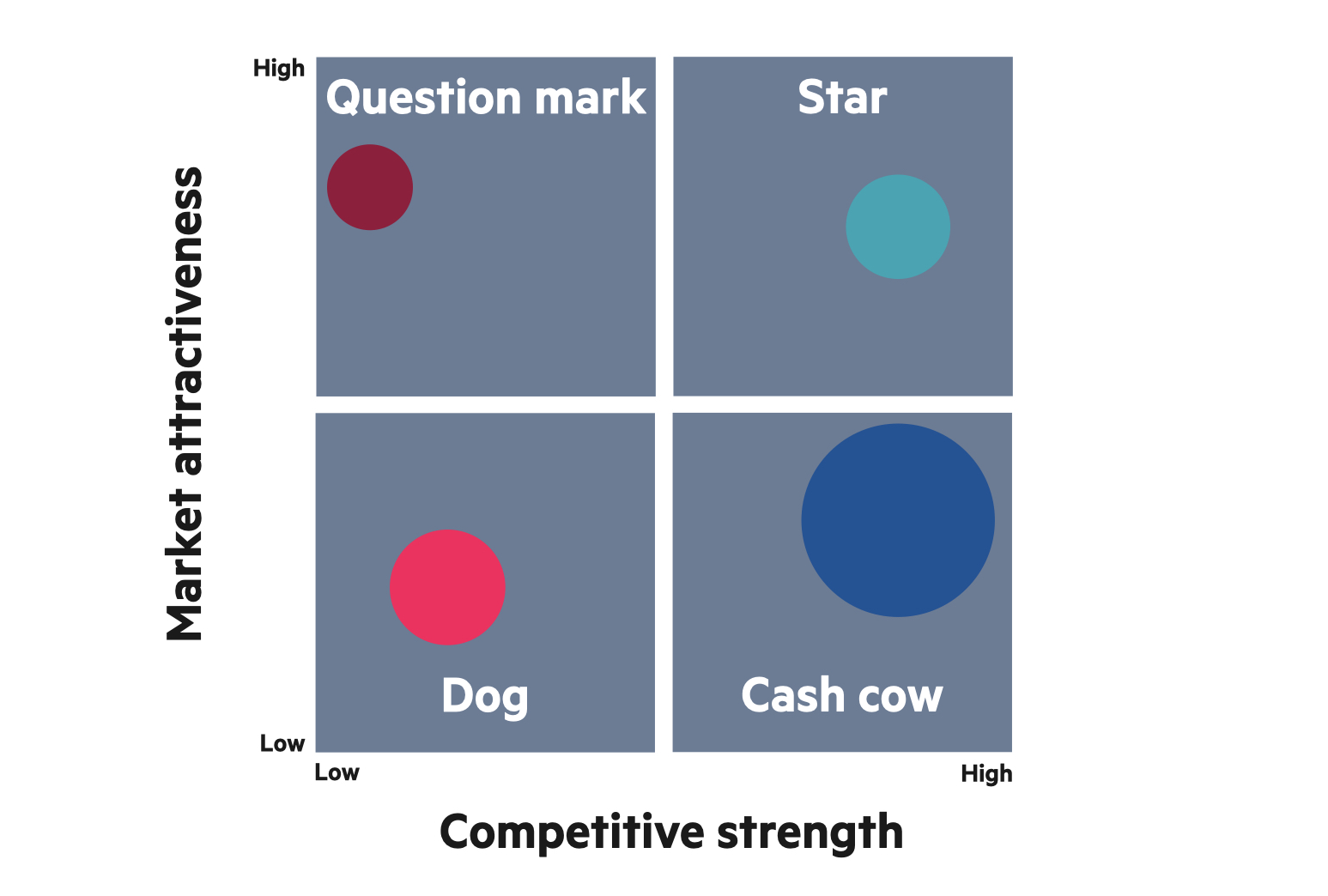

If you have a number of products in your portfolio you can do a portfolio analysis. One way to do this is the BCG (Boston Consulting Group) matrix. Based on what you know from your previous analyses on products’ life-cycles, risk and where they might be headed, you put them on a chart. The size of the bubble is the amount of revenue/profit they generate, and you can add an arrow for where they are headed. The four quadrants are:

- Star: a product with a strong position in an attractive market.

- Question mark: a product with a weak position in an attractive market; there are questions about market growth, sustainability, etc.

- Cash cow: a product with a strong position in a less attractive market. High share and lower costs than competitors means the product becomes a cash provider.

- Dog: a weak position in a less attractive market.

Products are not static. For example, a cash cow won’t always stay that way; a favourite example being Kodak, who didn’t anticipate (or couldn’t act on) people starting to share photos online rather than printing them out.

SWOT

Another way to bring it all together is the model that most of us are familiar with: SWOT: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats.

One great thing about this course was that they strongly said you should not do this first. As a tool on its own it is too blunt. But it’s great for pulling together all the other analyses once you have done them.

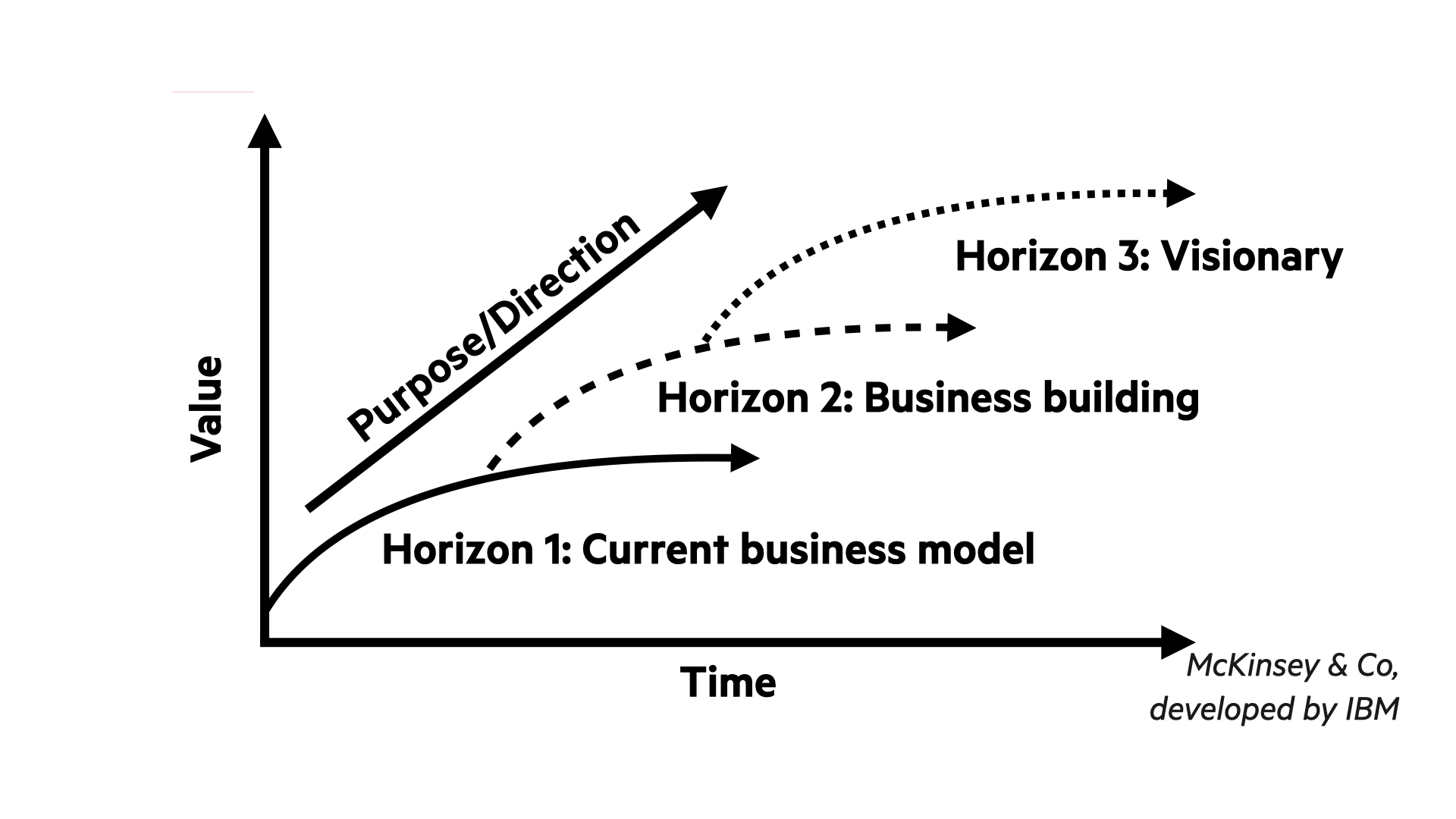

Three horizons

Once you’ve finished your analysis you need to decide what to do.

One tool for this is three horizons. No matter how effective the current business model is, it will change; it only represents a single point in time. Three horizons is looking towards the next business models.

Horizon 1: Current business model

Making the most of the current business model.

Horizon 2: Business building

A significant change from one business model to the next. When it’s embedded, horizon 2 becomes the new horizon 1.

Horizon 3: Visionary

Exploring and investing in new ideas that might be unproven and unprofitable for a significant period of time, usually years. The horizon 3 investments that show promise may form part of an eventual horizon 2.

The board should be thinking on 3 horizons simultaneously, in line with their vision/purpose.

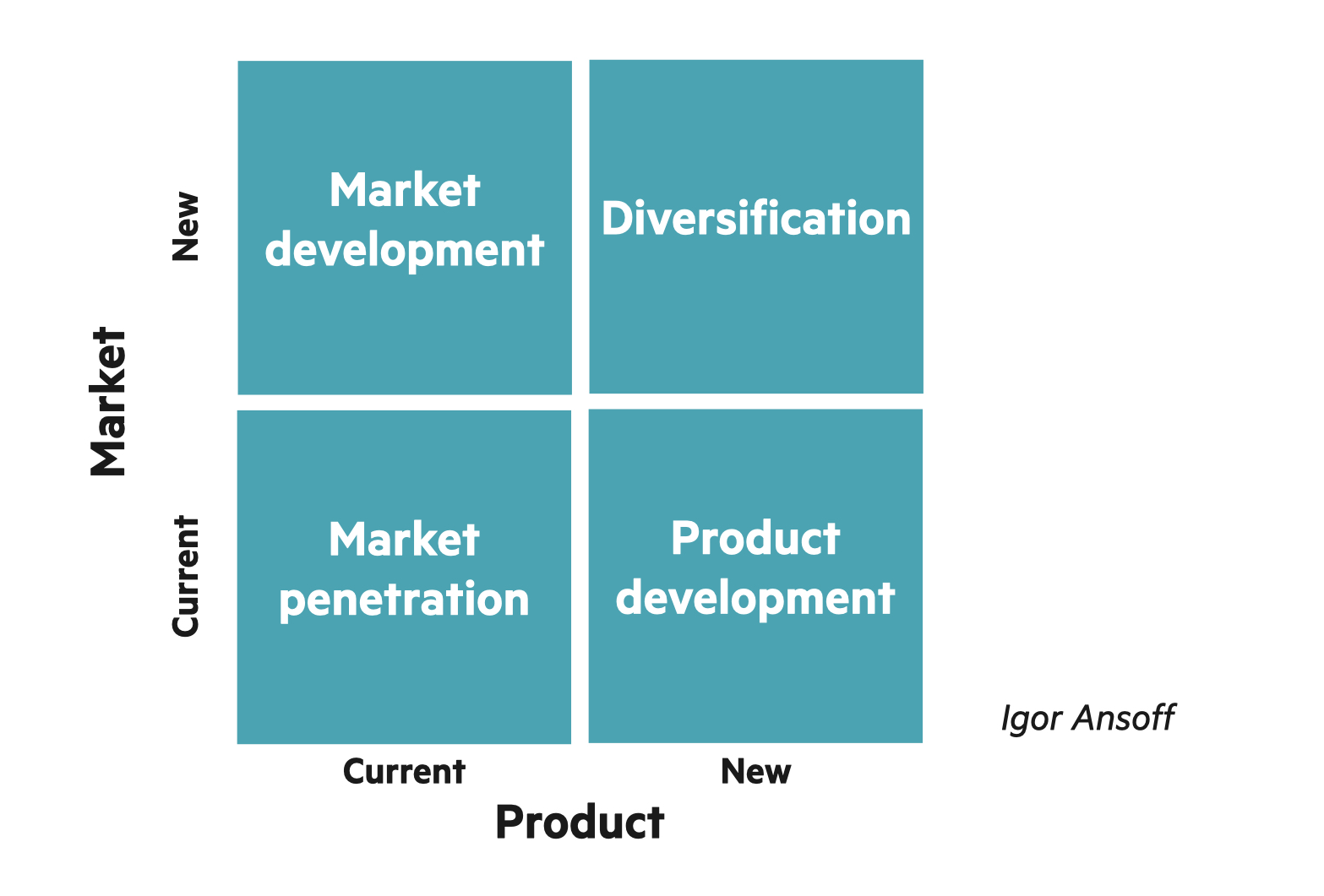

Ansoff matrix

The Ansoff matrix can be used to chart the four main options for strategic growth. Growth can only come from two places: more or more valuable customers (markets), or more or more valuable products/solutions.

- Market penetration Existing customers, existing product: increase usage or steal from the competition.

- Market development Take existing product to new markets or new segments.

- Product development Develop new products for your existing market.

- Diversification Develop a new product for a new market. This is the riskiest strategy because both are new. The Xbox from Microsoft (new product and new market, from business customers to gamers) is a successful example but there are plenty of examples that failed, and even some that brought the company down.

Note that people often use “diversify” in conversation to mean product or market development. True diversification is both.

Blue Ocean approaches

The ‘Blue Ocean’ strategy from Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, is about focusing on uncontested space in the market (‘blue’ as contrasted with ‘red ocean’, coloured by blood of competitors!).

It is about creating new ‘value factors’ that haven’t been identified by any competitors, and then using those to attract markets who do not engage with competitors’ similar products. The classic example is the Nintendo Wii. Instead of competing with Microsoft and Sony for bigger and better GPUs it instead focused on motion controllability, saving money on every other aspect of the console and attracting a new market not previously into gaming, making it more of a family activity (think of Wii bowling).

The value factors have to be strong enough to change customer behaviour, and they also may not be defensible; competitors may also capitalise. However, it’s a good idea for boards to have Blue Ocean discussions, even though it is not necessarily easy.

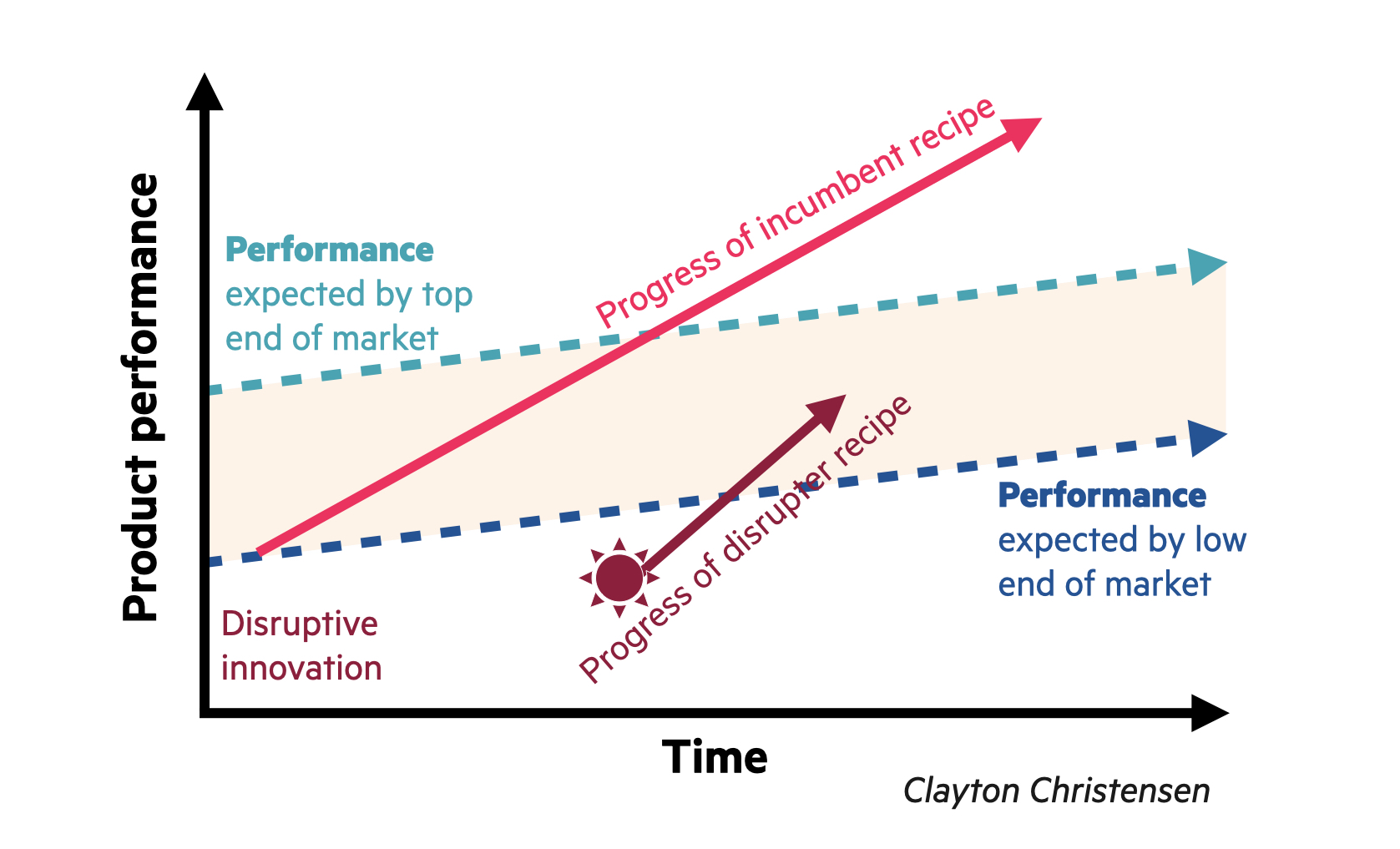

Disruptive innovation

The principle of disruptive innovation, as outlined by Clayton Christensen, is that established players may build in functionality that is over and above what is required by the market. A new player may come in, typically created by the novel intersection of two industries, and offer a recipe that has less functionality than offered by the established players. Because it’s simpler, it may be more affordable, and it may appeal to new or overlooked market segments.

Initially it is rarely high-performing. However, it has potential, and once it has disrupted the market, the damage is done. Usually the first-mover is not the one to benefit from the disruption but actually a fast second-mover. However, the act of the first move typically disrupts the industry irreversibly and in effect stimulates a new industry evolution ‘S-curve’, rendering the entire established sector redundant.

SAFe (no, not that one!)

When you’ve come up with ideas you need to decide what to do. One model to use is that the solution should be SAFe. Not scaled agile framework; but Suitable, Accessible, Feasible.

Suitable: Does it fit the mission, is it profitable, does it accord with the strategic analysis? Does it respond to the main challenge the organisation faces?

Acceptable: Is it within the level of risk accepted by the organisation? Will it be acceptable to customers, markets, employees, shareholders, etc? Does it meet fundamental values? Stakeholder analysis is important as strategic options without stakeholder buy-in are unlikely to succeed.

Feasible: Does the organisation have the capability in terms of resources (people, money, information)? Is the finance available over the strategic term? etc

Weighting and scoring

To choose between options you can use a weighting and scoring tool. You identify some screening criteria for each option, and assign a score to each one.

For example, if you are deciding between getting a cat or a dog. You might choose screening criteria of how devoted the pet will be to you, how much care it will require, and whether the cost suits your pocket. You then assign each a score out of ten and add them up.

| Criteria | Dog | Cat |

|---|---|---|

| Devotion | 9 | 3 |

| Independence | 3 | 8 |

| Cost | 4 | 6 |

| 16 | 17 |

You can also weight it, for example, how independent the pet is might be the most important factor for you, so you might double or treble that score.

This can help decide between strategic options by identifying what the key criteria are. Again, the value of this tool is very much to support the discussion rather than just add up the scores.

Implementation web

The last model to talk about is how you are implementing the strategy.

The exercise here is to score each of the following on a scale of 0-10. The resulting diagram shows where the ability to implement is strong and weak, and can also show where there is alignment and not by comparing scores of different team members.

- People Do we have the right calibre of people, in the right roles, with the right knowledge and skills?

- Business case Do staff know what the strategy is, understand it and find it meaningful?

- Communicate Are there regular communications about success, good practice and lessons learned? Do staff know what they need to do to implement the strategy?

- Measure Have measures been agreed to track the progress of the strategy and do the measures drive the right behaviours?

- Culture How well does the current culture support the strategy and have leaders changed the way the organisation works and behaves to encourage adoption of the strategy?

- Process Do processes and structures support the new strategy and have we redesigned processes?

- Reinforce When staff members demonstrate new behaviours and actions, are they recognised and rewarded, and do leaders lead by example?

- Review Are people carrying out the required actions, do the actions produce the right results and do we adapt the strategy/implementation in light of lessons learned?

To be continued

In my next post I talk about how to tie these together and use these models in practice.

If you’d like to be notified when I publish a new post, and possibly receive occasional announcements, sign up to my mailing list: